Okay, maybe not absolutely EVERYTHING about Mount Garibaldi – the renowned geoscientists who have spent their lives dedicated to researching the Coast Mountains would be the experts for that! However, if you’re like us, novice geology geeks, this rundown of the features & subfeatures of Mount Garibaldi might just suffice. Mount Garibaldi (Nch’kaý) is more than just an epic peak we fly over, climb, or ski. The mountain and its surrounding features tell a story of destruction and creation, taking place over thousands of years. When we fly over this area, we see the striking result of the complex history of the landscape.

Mount Garibaldi is an iconic peak in the Squamish area, part of the Pacific Ranges of the Coast Mountains. Standing at 2,678 meters (8,781 feet) tall, it is surrounded by glaciers, peaks, alpine meadows, and lush forests. From its summit, one can take in the entire Howe Sound region, including Vancouver and the surrounding mountains, and even Vancouver Island on a clear day. Located on the east side of the Cheakamus River between Squamish and Whistler, Mount Garibaldi lies within the Pacific Ranges Ecoregion. This mountainous region of the southern Coast Mountains is characterized by high, steep and rugged mountains made of granitic rocks, and encompasses much of the Pacific Ranges in southwestern British Columbia, as well as the northwesternmost portion of the Cascade Range in Washington state. [1,2]

The geology of Mount Garibaldi is equally impressive and quite complex, composed of a variety of rock types including granite, gneiss, schist, and quartzite. These rocks were formed over millions of years as tectonic plates collided and pushed up the mountain range. The mountain also contains a variety of minerals including mica, feldspar, and quartz. [3]

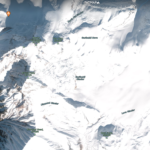

Mount Garibaldi is a volcanic mountain with three main summits and several notable, main features. The main peak goes without saying is Mount Garibaldi, while the two additional peaks are named Atwell Peak and Dalton Dome. Atwell Peak is a sharp, conical summit that is slightly higher than the more rounded summit of Dalton Dome. In addition to these epic peaks, the northern and eastern flanks of Mount Garibaldi are covered by the Garibaldi Névé, a large snowfield with several radiating glaciers.

Flowing from the steep, western face of Mount Garibaldi is the Cheekye River, a tributary of the Cheakamus River. On the southeastern flank of Mount Garibaldi, you’ll find Opal Cone, a small volcanic cone from which lengthy remnants of lava flow descend. And last, but certainly not least, is arguably one of the most striking views from the Squamish Valley. The western face of Mount Garibaldi is a landslide feature that was formed by collapses between 12,800 and 11,500 years ago, resulting in a large debris flow deposit that fans out into the Squamish Valley. [4,2]

The northern and eastern flanks of Mount Garibaldi are covered by the Garibaldi Névé, the main glacial feature of the volcano. Those who are extremely experienced in glacial travel might put the Garibaldi Névé Traverse on their winter objectives list. While the Garibaldi Névé might be the most well-known, there are several individually named outlet glaciers surrounding the Garibaldi Névé. These include:

Two glaciers, the Garibaldi and Lava, originate from the south side of the Garibaldi Névé and their sediment-filled waters flow into the Mamquam River. The Warren Glacier is located just north of Mount Garibaldi and flows towards the Cheakamus River. The combined area of the Garibaldi Névé and its outlet glaciers is approximately 30 square kilometres (12 square miles). Additionally, two other glaciers can be found on Mount Garibaldi: Cheekye Glacier south of the summit and Diamond Glacier between Atwell Peak and Diamond Head. [4,5]

Photo courtesy of FatMap Official